You toured with Unnatural Causes in 2022/3 and now you are going out on your second theatre tour this autumn, what is it that you like about touring?

I have always enjoyed talking to people and explaining what I do and why. I have spent a lot of time giving lectures to medical students, policemen, paramedics and the public and I’ve never found it difficult to speak to large groups so going on tour is just another way of trying to give people a little bit of an understanding about what we really do as so much of that work goes on in the background. Many people think that what I do is just destructive, and some people may think it is an awful thing to do, but my focus is always on finding the truth and then trying to make sure that the relatives understand. The truth may be difficult hear – but that is ultimately far less distressing that not knowing or having unanswered questions about the death of someone you are close to.

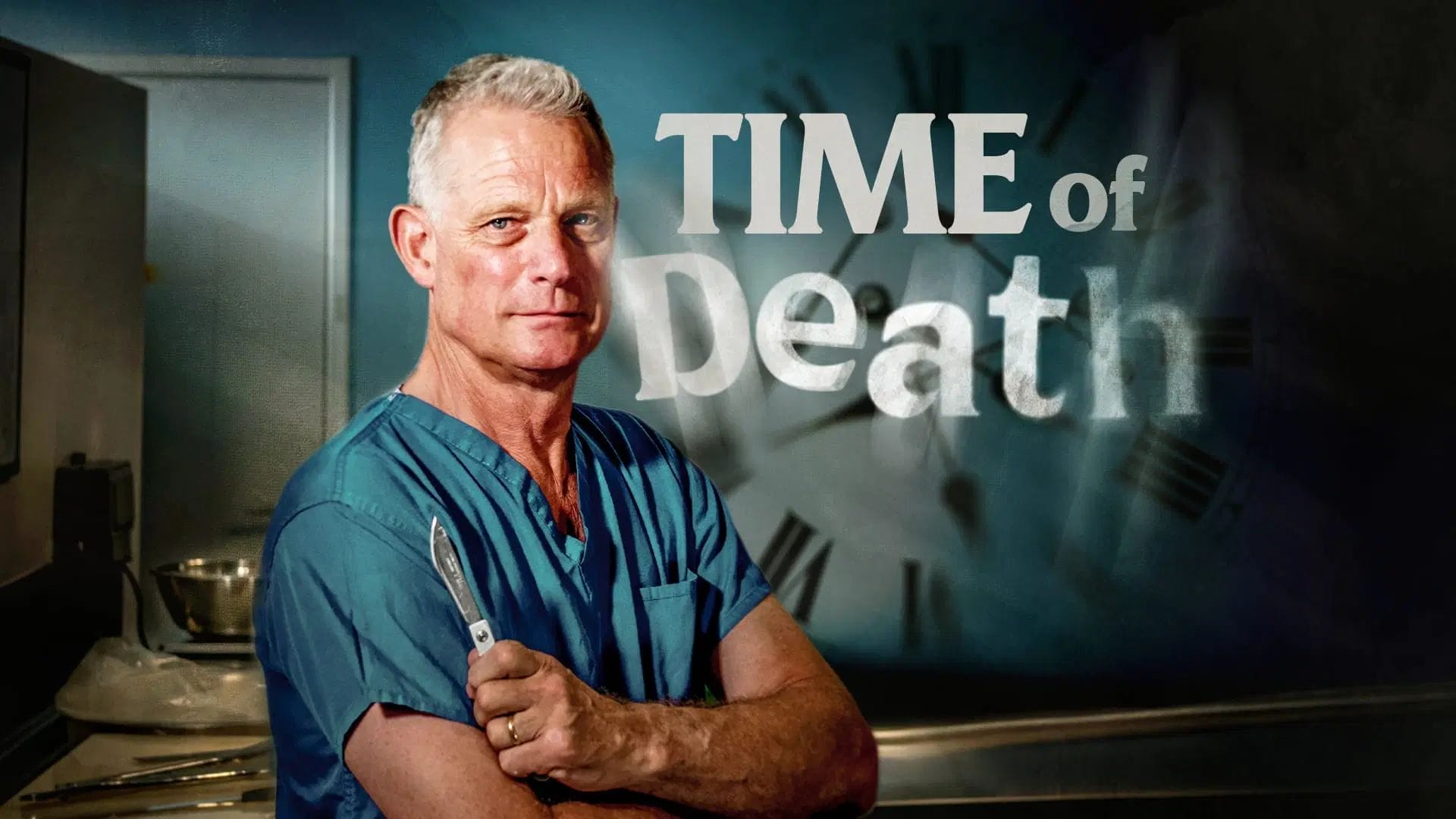

What can we expect from the new show, Time of Death – More Unnatural Causes

When I retired as a Home Office pathologist, I took up a long held interest in learning how to mend clocks and as someone pointed out I’d spent my whole career taking things apart and not being able to put them back together, and that mending clocks meant I was taking complex things apart in the hope that I could put them back together and get them to work again.

It made me think again about how time is so important in terms of forensic medicine. When did the crime happen? How old is that injury? How long did someone survive? All crucial questions.

So, we are going to be talking about the importance of time in forensic medicine using examples of some interesting and different cases that I have dealt with.

Have you ever had anybody in an audience become quite overcome or emotional during one of your shows?

Only one, and they had to leave – I could not help but notice as they were in the middle of the front row! But they did come to see me afterwards when I was signing books and we were able to have a little chat. A long time ago when I was lecturing senior police officers at Hendon Police College one of them collapsed and it did not look as if they were coming around, so I thought I had better see what was going on. As I got near, they in fact seemed OK, so I went back to my lectern muttering that “nobody wants to wake up from a faint to see a forensic pathologist leaning over them. Unfortunately, I had forgotten that my microphone was still switched on so the whole room heard what I had said to myself …. and cheered!! Years later I met that man again, who described himself as “the one person who escaped Dick Shepherd’s knife.”

You also appear on Channel 5’s Cause of Death, looking at cases at Preston Coroner’s Court, which shows how compassionate all the staff involved in sudden deaths are…

As a group of professionals we all do what might be considered an awful job, but we must always remember the people who are most important in the entire process are the relatives (and friends) of the person who has died. Obviously, I talk to my colleagues, the Coroner, and police officers about cases, and they are important too, but we have got to make sure the relatives understand, because if they do not, they worry and that can significantly add to their distress.

You have also recently been filming Body in Water which will air later this year on the True Crime – how do you explain the public’s huge interest in true crime on TV, and do you think women are more interested than men?

I think that people have always been both scared and fascinated by violent crimes – the victims, the perpetrators and those who must investigate them. Initially it was the “Penny Dreadful” magazines from 18th & 19th centuries with hand drawn dramatic pictures of the events and very descriptive stories. These were often sold at the time of the execution of the convicted perpetrator!! Nowadays we have more sophisticated magazines, books, and TV programmes to satisfy this interest, this continuing need to get into the nitty-gritty of how crime works! After the tours I have done and books I have written, I am fascinated that people are prepared to spend an evening listening to me! I am not sure of the demographic of the various audiences – I am just pleased to hopefully be able to show that there is empathy as well as investigation and punishment.

What kind of people go into professions such as yours where death is at the centre?

Most people I have ever come across working in in the ‘death’ industry are caring, conscientious and also very conscious of the complexities of what they are doing. Sadly, the fantasies held by the public, who are only touched by death a few times in their lives, can be very strong and are almost universally negative and we have to try to make sure that we treat them with empathy and respect at what is such a sensitive and difficult time

What made you interested in a career in pathology?

When I was about 13 a school friend of mine bought a forensic textbook by the celebrated pathologist Keith Simpson into school, and it suddenly opened my eyes to this whole intriguing world of murders, and I decided that that was what I wanted to do. I was not a stranger to death as my mum had died of heart disease when I was nine, so it was my dad who encouraged my interest in medicine. I only ever wanted to be a pathologist, but surprisingly, really enjoyed obstetrics and delivering babies but settled into a life of crime. I do appreciate how lucky I have been to have found a career that I enjoyed so much.

You grew up in Hertfordshire – can you tell us a bit about your childhood and school life before going to University?

My parents, my older brother and sister and I moved to Watford when I was five where I grew up. I went to a local primary school and then on to Watford Boys Grammar School where I was a “just about average” student eventually squeezing into St George’s medical school in London. I enjoyed playing sports, mainly swimming and rugby. I had an active social life with a group of friends centred around the local youth club. I was a Boy Scout for many years enjoying the adventures and outward-bound aspects – although camping never really appealed!

Your wife is in ‘the business’ too – how did you meet?

Linda my wife is a forensic doctor too – although she looks after living victims – and we met at a forensic meeting in London where I was lecturing and we spent time afterwards chatting about bruises. Very romantic! She declined my offer of a drink as she had to buy some shoes which defined my true place in the world. The rest, as they say, is history .. nearly 20 years and counting!

You now live in Cheshire – what made you move from the South?

I moved to Cheshire to be with Linda … simples!!

Did you find it difficult to balance your job and family life?

When the kids were younger this was very much an issue. If I had had a heavy day, I would stop the car around the corner from the house and spend a minute or two to mentally move myself from work mode to family mode. The kids always knew what I did and were not phased if the police came round to the house with bits and pieces to show me. In fact, one daughter has followed me into the profession. She and I chat quite frequently about cases, and it is nice having her as a close colleague, especially as she is a much better pathologist.

Do you have any other hobbies to relax?

I started flying when I met a CID officer when I was doing a postmortem who turned out to be an instructor for the Metropolitan Police Flying Club and who invited me to fly with them. I now fly a little Cessna, and a Piper Arrow, and it’s brilliant fun. We live in Cheshire, so I fly the Cessna out of Liverpool Airport. On nice weekend days Linda and I can put the dogs in their crates in the back of the plane and fly over the Wirral and Welsh mountains, past Anglesey down to Carnarvon – a trip which takes 2 hours by car but just half an hour by plane. We walk the dogs up and down the fabulous beach, have lunch, and then we fly home again. It’s fabulous! We’ve also be! up to the Scottish Isles, down to the Channel Islands, the Isle of Wight and over to France.

Tell us about your dogs? Are they really man’s best friend?

My two Jack Russells really are my best friends. They obviously can’t come to “proper” work with me, but they are constantly with me otherwise and certainly when I’m in my office writing reports. At the office they have two snug beds each next to a radiator and if I haven’t moved by about 3 pm the older one – Bertie – will come over and bark to remind me that it’s time for a walk! They are very tolerant and listen attentively when I go on about my difficult cases and they make sure I get an hour of exercise each day and if I sit down in the evening, they will join me to watch the television – although they do growl at Silent Witness!!

Are there any stand-out cases over your years that have never left you?

Obviously, cases that have a high public profile, like that of Princess Diana or David Kelly or Gareth Williams (The Spy in the Bag) or indeed many, many others, remain in the memory however it is often the smaller, more personal cases that leave a bigger permanent mark. In Unnatural Causes I wrote about a teenager who had epilepsy and died suddenly overnight. That case changed the way I interacted with bereaved families. There was also a case of a family who went to France on holiday; the mother and her 8-year-old daughter were crossing the road to go shopping, and the daughter didn’t look the correct way for French traffic, stepped out and was instantly killed. As a parent I still shiver at that thought. Lives can be changed in that fraction of a second and despite all my years as a forensic pathologist I just cannot imagine how you ever move on from that.

You have worked on mass disaster cases, including the 7/7 bombings in London, the Bali bombings, and the Hungerford Massacre. Do events like this in the news affect you?

The recent Air India crash was something I followed in the news. Managing the results of a mass disasters is a real skill, and it does distress me when I hear people speculating on these events and saying things like: “The families are going to be invited in to look at the bodies.” That’s definitely not what we do. Of course, we do need to establish identity and how the individual died but we do it in a really caring way that cherishes the families as best as we can. And that does not include inviting them to walk up and down rows of bodies in a mortuary until they happen to see their relative. Rather, we identify the individuals and then invite the family to see the body quietly and privately if they wish to do so and with emotional and psychological support – a process that can, if necessary, progress slowly and take many hours and be spread over several days.

Why are we obsessed with true crime, yet reluctant to discuss death?

Some people are very reluctant to believe that their relatives will / could ever die, no matter how old or ill they are, and when the inevitable happens they believe that something must have gone wrong. We no longer openly talk about “death” we talk euphemistically about ‘passing on,’ so people are no longer used to the experience of death and do not know how to behave in the face of sudden strong emotions. Not that long ago, the body would lie in the house before the funeral with family, neighbours and friends coming in to pay respect. I am struck by the public response to a member of the royal family “lying in state” which shows that there is still a need for that chance to say goodbye. The experience of death is now diminished so that when it does happen there have not been any rehearsals for what it is going to be like, and they struggle to understand their emotions which all make death much harder to cope with.

It must be difficult to reveal facts about someone who has died to relatives who did not know them before…

Sadly, quite a lot of the inquests I give evidence in are drug-related or are suicides, and families often say they tried hard to help but eventually failed, which is just awful, or say they never knew that their relative used drugs, or was planning suicide. It is hard either way, and I am not at all convinced that the formal Coronial system works well for the families in these instances. It is important that families know the truth even if it is a difficult truth and I feel that a much less formal environment would often be a better place to discuss and disclose these matters with the families rather than for them find out during the Inquest in the Coroner’s Court.

Is modern medicine changing the way postmortems are conducted?

Traditionally we examined cases using a formal dissection of the body however a number of Coroners will now use a postmortem CT scan for their initial examination of a body and, if a possible cause of death is seen, then no further examination will be performed. This system can work well and it avoids the dissection but it does not always give the full answer and, unless the coronial systems look for and consider all of the facts surrounding a death carefully, a PM scan may indicate A cause of death rather than THE cause of death. I do worry that in the rush to do things quickly and possibly cheaply there is a huge risk that valuable information may be missed. I know from my own postmortem examinations that I will not infrequently find something important the scans did not see!

You are a real advocate for communicating about medicine, is there anyone who inspired you to do that?

Dr Jonathan Miller taught me History of Medicine at UCL, and he was a fantastic polymath and communicator. What he taught was not directly to do with medicine, it was to do with history of medicine and philosophy. We discussed things like maintaining the balance between being a professional, academic, wise clinician knowing everything about everything but also remembering you are dealing with a patient who is utterly petrified and that you must manage that interface. He was a fascinating man.

With your TV appearances and theatre shows you really have become a part of the ‘showbiz world’ – did you have any childhood aspirations on this front?

I wasn’t a show-off as a child; the closest I got to showbiz was the medical school revue when I had to play Dracula and lie in a coffin (which we had borrowed from a local undertaker) and had driven it down Tooting High Street sticking out of the boot of my friend’s Mini! ,

What do you hope audiences will take away from your shows?

I like communicating and I love my subject, and audiences clearly enjoy it too.